Some cool sourcing china products images:

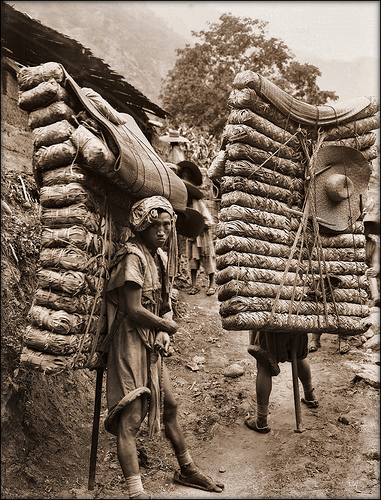

Men Laden With Tea, Sichuan Sheng, China [1908] Ernest H. Wilson [RESTORED]

Image by ralphrepo

Entitled: Men Laden With Tea Sichuan Sheng China JUL [1908] EH Wilson [RESTORED] Very little retouching except for a few scratches and spots. Minor contrast and sepia tone added. The original resides in Harvard University Library’s permanent collection, and can be found using their Visual Information Access (VIA) Search System by using the title.

Ernest Henry "Chinese" Wilson was an explorer botanist who traveled extensively to the far east between 1899 and 1918, collecting seed specimens and recording with both journals and camera. About sixty Asian plant species bear his name. One of his most famous photographs (above) has repeatedly been mistakenly attributed to another legendary botanist (Joseph Rock) who was also working in Asia.

From Wilson’s personal notations (with misspellings as is):

"Men laden with ‘Brick Tea’ for Thibet. One man’s load weighs 317 lbs. Avoird. The other’s 298 lbs. Avoird.!! Men carry this tea as far as Tachien lu accomplishing about 6 miles per day over vile roads, 5000 ft."

I suspect that Wilson made a mistake; either miscalculating a conversion from Chinese Imperial to European weight measure, or that he believed an inflated figure offered him by a less than honest native. However, others purportedly shared the same beliefs that some porters did in fact, carry upwards of 300 pound loads. In a rare 2003 interview with several retired former porters, still alive and in their 80’s. They stated that while the average was really more between 60-110 Kg; they acknowledged that some (only the very strongest) could shoulder a superhuman 150 Kg load; someone like Giant Chang Woo Gow, or one of his kin, perhaps? An excerpt about that interview:

"The Burden of Human Portage

As recently as the first decades of the 20th century, much of the tea transported by the ancient Tea-Horse Road was carried not by mule caravan, but by human porters, giving real substance to the once widely-employed designation ‘coolie’, a term thought to have been derived from the Chinese kuli or ‘bitter labour’. This was particularly true of smaller tracks and trails leading from remote tea-picking areas to the arterial Tea-Horse routes, both in Yunnan and in Sichuan. Perhaps because this human portage played a less economically significant role than the large – sometimes huge – yak, pony and mule caravans, and perhaps because there is little or no romance attached to the piteous sight of over-burdened, inadequately-clad and under-nourished porters hauling themselves and their massive loads across muddy valleys and freezing mountain passes, less information is available to us concerning tea porters than about tea caravans.

Fortunately some black-and-white images of these incredibly wiry, tough, hard-bitten men have come down to us from Sichuan, as well as at least one 150-year-old French-made lithograph from Yunnan, in addition to some rare oral accounts describing the immense difficulties these hardy wretches had to face. In the latter category, as recently as 2003 China Daily carried an interview with four former tea porters in Ganxipo Village, near Tianquan County to the southwest of Ya’an. Now in their 80s, these veterans recall hard times before the completion of the Sichuan-Tibet Highway in 1954 when they would carry almost impossibly heavy loads of Sichuan Pu’er tea over a narrow mountain trail across the freezing heights of Erlang Shan (‘Two Wolves Mountain’) to Luding and onwards, across the Dadu River, to the tea distribution centre at Kangding.

According to 81-year-old former tea porter Li Zhongquan, tea was carried by human portage all the way from Tianquan County to Kangding, a distance of 180km (112 miles) each way on narrow mountain tracks, much of the way at dangerously high altitudes in freezing temperatures. According to Li, an able-bodied porter would carry 10 to 12 packs of tea, each weighing between 6 and 9 kg. To this had to be added 7 to 8 kg of grain for sustenance en route, as well as ‘five or six pairs of homemade straw sandals to change on the way’. The strongest porters could carry 15 packs of tea, making a total load of around 150 kg (330 imperial pounds). ‘The grain lasted no longer than half the journey’, Li remembered, ‘and you had to replenish your food supply at your own expense’. As for the multiple pairs of straw sandals: ‘these would be worn out quickly, as the mountain path was extremely rough’.

To make the portage of such heavy loads possible, and to help guard against the ever-present danger of overbalancing and falling into one of the many deep ravines skirted by the narrow mountain trail, tea porters carried iron-tipped T-shaped walking sticks both to assist in struggling over the steep, rocky path, and to rest the load on, without taking it off their backs, when they paused for breath. A surviving section of the old stone path near Ganxipo Village bears testament to the almost unimaginable difficulties faced by the tea porters in the past; small holes dot the stone slabs of the path at regular intervals of a pace or so, indicating where, over centuries and perhaps even millennia, the porters struck the rock with their iron-tipped sticks as they made their laborious way to and from Kangding.

It is possible to identify the T-shaped walking-and-support sticks used by the tea porters in black and white photographs from a century or more ago, including one taken by the American explorer and botanist E.H. Wilson, who helpfully appends the information: ‘Western Szechuan; men laden with “brick tea” for Thibet. One man’s load weighs 317 lbs [144 kilos], the other’s 298 lbs [135 kilos]. Men carry this tea as far as Tachien-lu [Kangding] accomplishing about six miles per day over vile roads. Altitude 5,000 ft [1,500m] July 30, 1908’.

For the tea porters of Ganxipo Village, the hardest part of their journey was the climb over Erlang Shan. The precipitous mountain trail was so narrow that it was only wide enough for one person to pass at a time. According to Li Zhongquan: ‘one misstep, and you were gone – we had our sandals soled with iron to get over the mountain’. Li also remembers when: ‘one of us was sick and fell dead on the mountain top in winter. We had to leave him there until the snow thawed in spring, when we carried the body down home’. The porters carried tea from Tianquan to Kangding, and returned with loads of medicinal herbs (especially Cordyceps sinensis of Chinese caterpillar fungus), musk, wool, horn and other Tibetan products. The four porters interviewed in China Daily did not know for sure when the tea portage China trade had started in Ganxipo, but Li was certain that ‘my grandpa’s grandpa was a porter as well,’ and that the whole village had offered porter services for generations."

Source: www.cpamedia.com/trade-routes…l-perspective/

Just walking for a few kilometers on a flat surface with 40 Kg worth of material on your back, I can attest is already exhausting. To imagine tripling that weight, walk for over 180 kilometers over mountain trails, and breathe rarefied air? I wouldn’t say it’s downright impossible, but highly improbable. I too, would agree that it was likely only exceptions rather than the rule.

Barbers’ Garden, July 2008: Dorothy Perkins Rambling Rose

Image by bill barber

Looks like a reflection, but it’s not.

This scented rambling rose from 1901 features large clusters of bright pink dainty blooms with brightly polished green foliage. This rose can put on growth of 20ft in one season which makes it ideal for rambling up trees barns or buildings. The rose was named for the grand daughter of the founder of the nursery firm Jackson & Perkins.

www.rosesscotland.co.uk/ramblingrose.html

From my set entitled “Roses”

www.flickr.com/photos/21861018@N00/sets/72157607214064416/

In my collection entitled “The Garden”

www.flickr.com/photos/21861018@N00/collections/7215760718…

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rose

A rose is a perennial flowering shrub or vine of the genus Rosa, within the family Rosaceae, that contains over 100 species. The species form a group of erect shrubs, and climbing or trailing plants, with stems that are often armed with sharp thorns. Most are native to Asia, with smaller numbers of species native to Europe, North America, and northwest Africa. Natives, cultivars and hybrids are all widely grown for their beauty and fragrance. [1]

The leaves are alternate and pinnately compound, with sharply toothed oval-shaped leaflets. The plants fleshy edible fruit is called a rose hip. Rose plants range in size from tiny, miniature roses, to climbers that can reach 20 metres in height. Species from different parts of the world easily hybridize, which has given rise to the many types of garden roses.

The name originates from Latin rosa, borrowed through Oscan from colonial Greek in southern Italy: rhodon (Aeolic form: wrodon), from Aramaic wurrdā, from Assyrian wurtinnu, from Old Iranian *warda (cf. Armenian vard, Avestan warda, Sogdian ward, Parthian wâr).[2][3]

Attar of rose is the steam-extracted essential oil from rose flowers that has been used in perfumes for centuries. Rose water, made from the rose oil, is widely used in Asian and Middle Eastern cuisine. Rose hips are occasionally made into jam, jelly, and marmalade, or are brewed for tea, primarily for their high Vitamin C content. They are also pressed and filtered to make rose hip syrup. Rose hips are also used to produce Rose hip seed oil, which is used in skin products.

The leaves of most species are 5–15 centimetres long, pinnate, with (3–) 5–9 (–13) leaflets and basal stipules; the leaflets usually have a serrated margin, and often a few small prickles on the underside of the stem. The vast majority of roses are deciduous, but a few (particularly in Southeast Asia) are evergreen or nearly so.

The flowers of most species roses have five petals, with the exception of Rosa sericea, which usually has only four. Each petal is divided into two distinct lobes and is usually white or pink, though in a few species yellow or red. Beneath the petals are five sepals (or in the case of some Rosa sericea, four). These may be long enough to be visible when viewed from above and appear as green points alternating with the rounded petals. The ovary is inferior, developing below the petals and sepals.

The aggregate fruit of the rose is a berry-like structure called a rose hip. Rose species that produce open-faced flowers are attractive to pollinating bees and other insects, thus more apt to produce hips. Many of the domestic cultivars are so tightly petalled that they do not provide access for pollination. The hips of most species are red, but a few (e.g. Rosa pimpinellifolia) have dark purple to black hips. Each hip comprises an outer fleshy layer, the hypanthium, which contains 5–160 "seeds" (technically dry single-seeded fruits called achenes) embedded in a matrix of fine, but stiff, hairs. Rose hips of some species, especially the Dog Rose (Rosa canina) and Rugosa Rose (Rosa rugosa), are very rich in vitamin C, among the richest sources of any plant. The hips are eaten by fruit-eating birds such as thrushes and waxwings, which then disperse the seeds in their droppings. Some birds, particularly finches, also eat the seeds.

While the sharp objects along a rose stem are commonly called "thorns", they are actually prickles — outgrowths of the epidermis (the outer layer of tissue of the stem). True thorns, as produced by e.g. Citrus or Pyracantha, are modified stems, which always originate at a node and which have nodes and internodes along the length of the thorn itself. Rose prickles are typically sickle-shaped hooks, which aid the rose in hanging onto other vegetation when growing over it. Some species such as Rosa rugosa and R. pimpinellifolia have densely packed straight spines, probably an adaptation to reduce browsing by animals, but also possibly an adaptation to trap wind-blown sand and so reduce erosion and protect their roots (both of these species grow naturally on coastal sand dunes). Despite the presence of prickles, roses are frequently browsed by deer. A few species of roses only have vestigial prickles that have no points.

Roses are popular garden shrubs, as well as the most popular and commonly sold florists’ flowers. In addition to their great economic importance as a florists crop, roses are also of great value to the perfume industry.

Many thousands of rose hybrids and cultivars have been bred and selected for garden use; most are double-flowered with many or all of the stamens having mutated into additional petals. As long ago as 1840 a collection numbering over one thousand different cultivars, varieties and species was possible when a rosarium was planted by Loddiges nursery for Abney Park Cemetery, an early Victorian garden cemetery and arboretum in England.

Twentieth-century rose breeders generally emphasized size and colour, producing large, attractive blooms with little or no scent. Many wild and "old-fashioned" roses, by contrast, have a strong sweet scent.

Roses thrive in temperate climates, though certain species and cultivars can flourish in sub-tropical and even tropical climates, especially when grafted onto appropriate rootstock.

Rose pruning, sometimes regarded as a horticultural art form, is largely dependent on the type of rose to be pruned, the reason for pruning, and the time of year it is at the time of the desired pruning.

Most Old Garden Roses of strict European heritage (albas, damasks, gallicas, etc.) are shrubs that bloom once yearly, in late spring or early summer, on two-year-old (or older) canes. As such, their pruning requirements are quite minimal, and are overall similar to any other analogous shrub, such as lilac or forsythia. Generally, only old, spindly canes should be pruned away, to make room for new canes. One-year-old canes should never be pruned because doing so will remove next year’s flower buds. The shrubs can also be pruned back lightly, immediately after the blooms fade, to reduce the overall height or width of the plant. In general, pruning requirements for OGRs are much less laborious and regimented than for Modern hybrids.

Modern hybrids, including the hybrid teas, floribundas, grandifloras, modern miniatures, and English roses, have a complex genetic background that almost always includes China roses (R. chinensis). China roses were evergrowing, everblooming roses from humid subtropical regions that bloomed constantly on any new vegetative growth produced during the growing season. Their modern hybrid descendants exhibit similar habits: Unlike Old Garden Roses, modern hybrids bloom continuously (until stopped by frost) on any new canes produced during the growing season. They therefore require pruning away of any spent flowering stem, in order to divert the plant’s energy into producing new growth and thence new flowers.

Additionally, Modern Hybrids planted in cold-winter climates will almost universally require a "hard" annual pruning (reducing all canes to 8"–12" in height) in early spring. Again, because of their complex China rose background, Modern Hybrids are typically not as cold-hardy as European OGRs, and low winter temperatures often desiccate or kill exposed canes. In spring, if left unpruned, these damanged canes will often die back all the way to the shrub’s root zone, resulting in a weakened, disfigured plant. The annual "hard" pruning of hybrid teas, floribundas, etc. should generally be done in early spring; most gardeners coincide this pruning with the blooming of forsythia shrubs. Canes should be cut about 1/2" above a vegetative bud (identifiable as a point on a cane where a leaf once grew).

For both Old Garden Roses and Modern Hybrids, any weak, damaged or diseased growth should be pruned away completely, regardless of the time of year. Any pruning of any rose should also be done so that the cut is made at a forty five degree angle above a vegetative bud. This helps the pruned stem callus over more quickly, and also mitigates moisture buildup over the cut, which can lead to disease problems.

For all general rose pruning (including cutting flowers for arrangements), sharp secateurs (hand-held, sickle-bladed pruners) should be used to cut any growth 1/2" or less in diameter. For canes of a thickness greater than 1/2", pole loppers or a small handsaw are generally more effective; secateurs may be damaged or broken in such instances.

Deadheading is the simple practice of manually removing any spent, faded, withered, or discoloured flowers from rose shrubs over the course of the blooming season. The purpose of deadheading is to encourage the plant to focus its energy and resources on forming new offshoots and blooms, rather than in fruit production. Deadheading may also be perfomed, if spent flowers are unsightly, for aethestic purposes. Roses are particularly responsive to deadheading.

Deadheading causes different effects on different varieties of roses. For continual blooming varieties, whether Old Garden roses or more modern hybrid varieties, deadheading allows the rose plant to continue forming new shoots, leaves, and blooms. For "once-blooming" varieties (that bloom only once each season), deadheading has the effect of causing the plant to form new green growth, even though new blooms will not form until the next blooming season.

For most rose gardeners, deadheading is used to refresh the growth of the rose plants to keep the rose plants strong, vibrant, and productive.

The rose has always been valued for its beauty and has a long history of symbolism. The ancient Greeks and Romans identified the rose with their goddesses of love referred to as Aphrodite and Venus. In Rome a wild rose would be placed on the door of a room where secret or confidential matters were discussed. The phrase sub rosa, or "under the rose", means to keep a secret — derived from this ancient Roman practice.

Early Christians identified the five petals of the rose with the five wounds of Christ. Despite this interpretation, their leaders were hesitant to adopt it because of its association with Roman excesses and pagan ritual. The red rose was eventually adopted as a symbol of the blood of the Christian martyrs. Roses also later came to be associated with the Virgin Mary.

Rose culture came into its own in Europe in the 1800s with the introduction of perpetual blooming roses from China. There are currently thousands of varieties of roses developed for bloom shape, size, fragrance and even for lack of prickles.

Roses are ancient symbols of love and beauty. The rose was sacred to a number of goddesses (including Isis and Aphrodite), and is often used as a symbol of the Virgin Mary. ‘Rose’ means pink or red in a variety of languages (such as Romance languages, Greek, and Polish).

The rose is the national flower of England and the United States[4], as well as being the symbol of England Rugby, and of the Rugby Football Union. It is also the provincial flower of Yorkshire and Lancashire in England (the white rose and red rose respectively) and of Alberta (the wild rose), and the state flower of four US states: Iowa and North Dakota (R. arkansana), Georgia (R. laevigata), and New York[5] (Rosa generally). Portland, Oregon counts "City of Roses" among its nicknames, and holds an annual Rose Festival.

Roses are occasionally the basis of design for rose windows, such windows comprising five or ten segments (the five petals and five sepals of a rose) or multiples thereof; however most Gothic rose windows are much more elaborate and were probably based originally on the wheel and other symbolism.

A red rose (often held in a hand) is a symbol of socialism or social democracy; it is also used as a symbol by the British and Irish Labour Parties, as well as by the French, Spanish (Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party), Portuguese, Norwegian, Danish, Swedish, Finnish, Brazilian, Dutch (Partij van de Arbeid) and European socialist parties. This originated when the red rose was used as a badge by the marchers in the May 1968 street protests in Paris. White Rose was a World War II non violent resistance group in Germany.

Roses are often portrayed by artists. The French artist Pierre-Joseph Redouté produced some of the most detailed paintings of roses.

Henri Fantin-Latour was also a prolific painter of still life, particularly flowers including roses. The Rose ‘Fantin-Latour’ was named after the artist.

Other impressionists including Claude Monet and Paul Cézanne have paintings of roses among their works.

Rose perfumes are made from attar of roses or rose oil, which is a mixture of volatile essential oils obtained by steam distilling the crushed petals of roses. The technique originated in Persia (the word Rose itself is from Persian) then spread through Arabia and India, but nowadays about 70% to 80% of production is in the Rose Valley near Kazanluk in Bulgaria, with some production in Qamsar in Iran and Germany.[citation needed]

The Kaaba in Mecca is annually washed by the Iranian rose water from Qamsar. In Bulgaria, Iran and Germany, damask roses (Rosa damascena ‘Trigintipetala’) are used. In the French rose oil industry Rosa centifolia is used. The oil, pale yellow or yellow-grey in color, is sometimes called ‘Rose Absolute’ oil to distinguish it from diluted versions. The weight of oil extracted is about one three-thousandth to one six-thousandth of the weight of the flowers; for example, about two thousand flowers are required to produce one gram of oil.

The main constituents of attar of roses are the fragrant alcohols geraniol and l-citronellol; and rose camphor, an odourless paraffin. β-Damascenone is also a significant contributor to the scent.

Quotes

What’s in a name? That which we call a rose/By any other name would smell as sweet. — William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet act II, sc. ii

O, my love’s like a red, red rose/That’s newly sprung in June — Robert Burns, A Red, Red Rose

Information appears to stew out of me naturally, like the precious ottar of roses out of the otter. Mark Twain, Roughing It

Hearts starve as well as bodies; give us bread, but give us roses. — James Oppenheim, "Bread and Roses"

Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose — Gertrude Stein, Sacred Emily (1913), a poem included in Geography and Plays.