Check out these sourcing from china risks images:

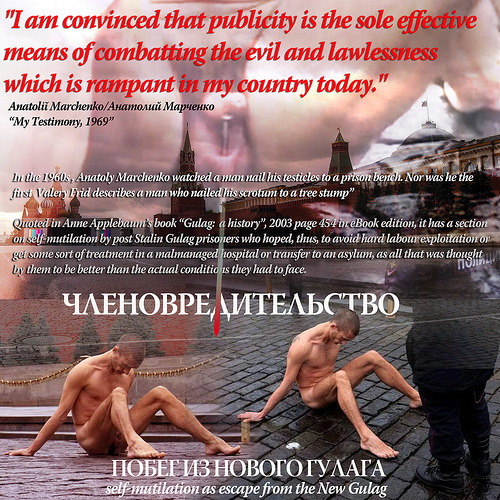

ARTIST WITH BALLS ON RED SQUARE: an attempt at understanding the self-mutilation protest of Pyotr Pavlensky

Image by Imaginary Museum Projects: News Tableaus

ARTIST WITH BALLS ON RED SQUARE: an attempt at understanding the self-mutilation protest of Pyotr Pavlensky

SELF-MUTILATION as ESCAPE FROM THE NEW GULAG

an attempt at understanding the artistic protest of Pyotr Pavlensky on the Red Square in Moscow, who nailed his scrotum to the pavement in front of the Mausoleum of Lenin and the Kremlin walls, yesterday. Shortly after he was cut loose and arrested for his deed. Pavlensky said his action was to "protest against the Kremlin’s crackdown on political rights." (1)

Self-mutilation in public has a long and varying history and a diverting set of meanings. The re-enactment of the crucifixion of Jesus Christ is performed in many places all over the world. The Islam knows the self-whipping men parading through the streets. Fakirs show their overcoming of the body by the mind by all kind of piercing actions. Piercing of body parts is of all times, often as an act of initiation or embellishments of the body. Modern art has a whole a whole score of body art, whereby some form of self-mutilation is performed, from the enactment of (self)castration by the Austrian artists Herman Nitsch and Rudolf Schwarzkogler, to the suspending in space of his body through wires and hooks in his skin by the Cypriot-Australian artist Stelarc.

All these examples differ in meaning from the action of Pyotr Pavlensky yesterday on Red Square, in front of the walls of the Kremlin and the Mausoleum of Lenin. His action points to the self-mutilation of soldiers and prisoners who try to escape from their dire situation, who are so desperate to get out of their actual situation that they re willing to hurt themselves, even badly. Soldiers that shoot themselves in the hand or leg (a common occurrence during the long lasting trench warfare of World War I, prisoners that try to poison themselves, harm their body or twist their mind and behavior in such a way, that they may be transferred to a hospital or a mad house. In the case of the long history of the Russian deportation camps from the time of the Tzars to the Stalin period and even beyond that, an attempt to escape to some form of hospital was a desperate act indeed, as the medical facilities in most of the Gulag camps was below any standard and in some cases more hellish than the actual concentration camp itself.

Nailing down oneself with a pin through the scrotum, between the balls, has been registered by several witnesses, and such examples did appear again in recent anthology of testimonies on the Russian Gulag by Anne Applebaum, published in the year 2003:

"A prisoner tells the story of a thief who cut off four fingers of his left hand. Instead of being sent to a field as invalid, however, did sit invalid snow and seeing others work. Forbidden to leave, afraid of being shot for attempted escape, "he soon himself and asked for a shovel, using it as a crutch, with his hand survivor, put it in the frozen ground, weeping and cursing. " Still, many prisoners felt that the potential benefit they made was worth the risk. Some methods were rude. The criminals were particularly known for his simply cut three fingers intermediates with an ax, so that they could not cut more trees or hold a wheelbarrow in the mines. Others cut off a foot or a hand, or rubbing acid in his eyes. Others still, to leave for work, a wet cloth wrapped around the foot, at night, came back with frostbite of the third degree. The same method could be applied to the fingers.

In 1960, Anatoly Marchenko saw a man preaching his testicles in a bank in prison. It was not the first: Valerii Frid describes a man who preached his scrotum in a tree stump."

[Applebaum, Anne. 2003. Gulag: a history. New York: Doubleday; pafge 445 in the eBook edition I used]

The use of the verb ‘preached’ is odd, and hardly used in English, as far as I could ascertain. I took the quotation on line, once more from Google Books and there another rendering of this sentence is given:

"In the 1960s , Anatoly Marchenko watched a man nail his testicles to a prison bench. Nor was he the first Valery Frid describes a man who nailed his scrotum to a tree stump.” (2)

It seems that the action of Pyotr Pavlensky did find its inspiration source right there. Or, if not so, it is a way to read his action, as it is not only the actor who determines how others perceive his performance.

However gruesome the act – piercing a long nail through the tender skin of the scrotum straight between the most sensitive part of a man’s body, his balls onto the cold pavement of a huge square – it is still a few steps away from the public sacrifice of one’s life. Self-immolation is such a final act, being of another order. It can hardly be called an ‘artistic act’ when one drowns one’s own cloths and body in an inflammable liquid and sets it afire. Examples galore with certain strains of Buddhism and Hinduism accepting this form of self-sacrificing acts. Russia has its own horrid history with the persecution of the ‘old believers’ in the 17th century, whereby whole villages in fear of a horrid end at the hands of their persecutors preferred to burn themselves to death, in what was called their ‘fire baptism’.

The most recent political use of self-immolations were in Bulgaria in a protest against the against the Borisov government. The protest of a Tunisian street vendor, Tarek al-Tayeb Mohamed Bouazizi, against his maltreatment in December 2010 triggered in the end the Arab Spring movement and when we move back through time we meet Tibetans, Czechs and Vietnamese monks that use this form of ultimate protest.

Back to the action on the Red Square and the intent and effect of such actions. It was not Pavlensky ‘s first radical action. Another one was preceding it. As is explained on a Wikipedia page about this artist:

"By suturing my mouth on the background of the Kazan Cathedral, I wanted to show the position of the artist in contemporary Russia: a ban on publicity. I am sickened by intimidation of society, mass paranoia, manifestations of which I see everywhere." While commenting on the questionable originality of his action in one of the later interviews, Pavlensky mentioned: "Such practice has occurred among artists and prisoners, but for me it did not matter. The question of primacy and originality here for me does not exist. There was no goal to surprise anyone or come up with something unusual. Rather, I felt the necessity to make a gesture that would accurately reflects my situation."[Wikipedia Petr Pavlensky ]"

Does nailing your balls to the pavement of the most central and symbolic square of Russia "reflects accurately" the situation in Russia in general, or does the desperate act only reflect the state of mind of the artist? As a non-Russian it is impossible to come up with an answer, still there is no doubt that Russia of today is a society which carries it’s repressive and violent past with it, like all powerful nations do. When reading the nailing action from the perspective of the Gulag history, the artist is willing to risk – at least – parts of his body, in order to escape from what he feels to be his imprisonment within the confines of a society full of paranoia. Self-mutilation was seen as a crime within the Gulag system. It could be heavily punished. Refusal to fit as an exploitable part within the Gulag (production system), could lead to a death sentence, however paradoxical that may seem. Pavlensky has already been arrested and examined to see if he would not better fit in the infamous Russian classification system of those who are mentally ill. After his action with sewing his lips, he did get out, and was declared sane. The question is if he will be so ‘lucky’ next time.

One may also question whether the need for dramatic acts, grandiose symbolic performances that aim at the heart of the power system, is what will change the system. Grotesque gestures seem to me – as an outsider – an expression of the bombast of power as displayed by Tzars, Party Secretaries and other ‘great leaders’, a cultural phenomenon that has been aptly named in new-speak of the last century: ‘Palast-Kult’. The artist as martyr for the great cause of the Great Russia… I see analogies with the the style of the National Bolshevik Party of Eduard Limonov and their need and ways to produce martyrdom (like the recent case of the bad luck of Alexander Dolmatov asking for political asylum in the Netherlands, that treated him so badly that he ends up committing suicide in a Dutch prison cell).

Can the opponents of a power system be more than a reaction movement, mirroring in their actions and gestures the system they are fighting? One needs a lot of imagination to see any relationship between the ‘nailed down balls’ of the artist Pyotr Pavlensky and the ‘free roaming big balls’ of the ruler Vladimir Putin. The fragility of the male apparatus may do the trick: that is what the ruler and those who are overruled do have in common. We know that one day – at a moment least expected – the fragility of yet another ‘big ball system’ will come to the fore and what seemed most strong proves to be weak.

Maybe there is yet another association: what seems to be omnipotent is nailed down so much to all those strata of society that try to secure their interest and extend their control with such a force that there remains no more free roaming for potent policy. ‘The potentate’ is constantly pulled from one side to the other, until his scrotum can not withstand the contradicting forces exerted on it and it tears apart… leading to a collapse of what once was the towering pride of the ruler.

=====

(1) There are several video versions on YouTube, comparing them I choose this (sensational kind of web site) but good version of a video registration, without initial advertisement and so on. One has to click first to agree not to be younger than 18 years. This is the caption:

"Guy nails his scrotum to the ground as protest against police brutality Artist Peter Pavlensky nailed his testicles to a nail on the cobblestones of Red Square, the correspondent of "Fringe."The action is timed to the Day of Police, which is celebrated on November 10. The action began at 13:00. Around 14:30 the artist was taken by ambulance to the First City Hospital. After going to the hospital to deliver him to the police station, "China Town". In a statement about the artist’s action, called "Freeze", it is noted that it can be regarded as a "metaphor of apathy and political indifference and fatalism of the modern Russian society." Pavlensky known for other high-profile protests. May 3 this year, he went to the building of the Legislative Assembly of St. Petersburg naked and wrapped with barbed wire. Campaign "Carcass" symbolized "man’s existence in a repressive legal system, where any movement causes severe reaction of the law, bites into the body of an individual." In July last year Pavlensky held a rally in support of prisoners participating Pussy Riot. He sewed his mouth and stood at the Kazan Cathedral with a placard "Speech Pussy Riot has been famous action replay of Jesus Christ (mf.21 :12-13)."http://www.liveleak.com/view?i=777_1384084283"

(2) Anne Applebaum cites Anatoly Marchenko’s book "MY Testimony" (trad. Michael Scammel, London, 1969). I see that the eBook edition (what a shame does have neither page numbers nor foot- or end notes, so I can not give here the right page number.) Let me give at least a link to worldcat.org, as many libraries in the world do stock this book in one of the many editions that exist.http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/16922410

Added on 15/5/2014: I took the book from the library and had it laying around (and prolungued) for months, other things came in between, but today I phoographed, the pages from Marchenko’s book and took out the text by OCR. Here is the full passage which is relevant to this case:

Chapter: Self-Mutilation

–

"Here is one out of a number of similar stories, from which it differs only in its originality. It took place before my very own eyes in the spring of 1963. One of my cell-mates, Sergei K., who had been reduced to utter despair by the hopelessness of various protests and hunger strikes and by the sheer tyranny and injustice of it all, resolved, come what may, to maim himself. Somewhere or other he got hold of a piece of wire, fashioned a hook out of it and tied it to some home-made twine (to make which he had unravelled his socks and plaited the threads). Earlier still he had obtained two nails and hidden them in his pocket during the searches. Now he took one of the nails, the smaller of the two, and with his soup bowl started to hammer it into the food flap – very, very gently, trying not to clink and let the warders hear – after which he tied the twine with the hook to the nail. We, the rest of the cons in the cell, watched him in silence. I don’t know who was feeling what while this was going on, but to interfere, as l have already pointed out, is out of the question: every man has the right to dispose of himself and his life in any way he thinks fit.

–

Sergei went to the table in the middle of the room, undressed stark naked, sat down on one of the benches at the table and swallowed his hook. Now, if the warders started to open the door or the food flap, they would drag Sergei like a pike out of a pond. But this still wasn’t enough for him: if they pulled he would willy-nilly be dragged towards the door and it would be possible to cut the twine through the aperture for the food flap. To be absolutely sure, therefore, Sergei took the second nail and began to nail his scrotum to the bench on which he was sitting. Now he hammered the nail loudly, making no attempt to keep quiet. It was clear that he had thought out the whole plan in advance and calculated and reckoned that he would have time to drive in this nail before the warder arrived. And he actually did succeed in driving it right in to the very head. At the sound of the hammering and banging the warder came, slid the shutter aside from the peephole and peered into the cell. All he realized at first, probably, was that one of the prisoners had a nail, one of the prisoners was hammering a nail! And his first impulse, evidently, was to take it away. He began to open the cell door; and then Sergei explained the situation to him. The warder was nonplussed.

–

Soon a whole group of warders had gathered in the corridor by our door. They took turns at peering through the peephole and shouting at Sergei to snap the twine. Then, realizing that he had no intention of doing so, the warders demanded that one of us break the twine. We remained sitting on our bunks without moving; somebody only poured out a stream of curses from time to time in answer to their threats and demands. But now it came up to dinner time, we could hear the servers bustling up and down the corridor, from neighbouring cells came the sound of food flaps opening and the clink of food bowls. One fellow in the cell could endure it no longer – before you knew it we’d be going without our dinner – he snapped the cord by the food flap. The warders burst into the cell. They clustered around Sergei, but there was nothing they could do: the nail was driven deep into the bench and Sergei just went on sitting there in his birthday suit, nailed down by the balls. One of the warders ran to admin to find out what they should do with him. When he came back he ordered us all to gather up our things and move to another cell.

–

I don’t know what happened to Sergei after that. Probably he went to the prison hospital – there were plenty of mutilated prisoners there: some with ripped open stomachs, some who had sprinkled powdered glass in their eyes and some who had swallowed assorted objects – spoons, toothbrushes, wire. Some people used to grind sugar down to dust and inhale it until they got an abscess of the lung .. . Wounds sewn up with thread, two lines of buttons stitched to the bare skin, these were such trifles that hardly anybody ever paid attention to them. The surgeon in the prison hospital was a man of rich experi- ence. His most frequent job was opening up stomachs, and if there had been a museum of objects taken out of stomachs, it would surely have been the most astonishing collection in the world."

[Marchenko, Anatoliĭ, and Michael Scammell. 1971. My testimony. Harmondsworth, Eng: Penguin Books. ; p. 138-141. www.worldcat.org/oclc/562119565 ]

00uzbekistan 538 -1 SAMARKANDA MADRASA SHER DOR AÑO 1636 PLAZA DE REGISTAN

Image by Jose Javier Martin Espartosa

fuente: www.revistaviajar.es/nuestras-propuestas/mundo/articulos/…

Los ásperos territorios de Asia Central parecen condenados a brillar en lapsos de su historia para volver a diluirse en el más absoluto misterio, aunque Samarkanda, uno de los epicentros de la Ruta de la Seda que canalizara el intercambio de mercancías y saberes entre Oriente y Occidente, nunca se haya distanciado de ese mapa de geografías míticas que suena como música para el oído del viajero.

No es fácil estar a la altura de un nombre como Samarkanda, tan inflado de mito que se corre el riesgo de perderle la pista por los vericuetos de esas geografías imaginarias que arrancan en la Atlántida y ponen rumbo a Shangri-La o el país de las amazonas. El suyo, sin embargo, es a la fuerza un mito muy con los pies en la tierra, porque durante siglos se las ha visto y deseado para sobrevivirle a los altibajos que le tenía reservado el destino.

Como el resto de la hoy llamada Asia Central, Samarkanda ocupa la región del planeta que está más alejada de cualquier mar. Cercada de altas montañas, estepas y desiertos de temperaturas pavorosas que pasaron de ser una ruta obligada para el comercio entre China y el Mediterráneo a convertirse en una barrera en cuanto, a partir del siglo XV, la Ruta de la Seda comenzó a languidecer lentamente al imponerse las rutas marítimas para mercadear con Oriente.

Europa le dio entonces la espalda a estas tierras de clara herencia nómada, y no volvió a dirigirles mayor atención hasta que británicos y rusos, ya en el siglo XIX, se enzarzaron en un pulso por extender su infl uencia entre los 3.000 kilómetros que separaban las fronteras zaristas de la India colonial.

Hoy, tras décadas de aislamiento comunista, el Uzbekistán surgido como país independiente al desmembrarse la Unión Soviética en el año 1991 vuelve a asomarse a la escena internacional debido a las muchas implicaciones que tiene la proximidad de vecinos que, como China, Afganistán, Rusia o Irán, tampoco resultaban fáciles en los días de la Ruta de la Seda.

Al calor de las caravanas

Es sobre todo su rol de nudo caravanero el que alimenta el mito de Samarkanda, aunque desde luego no es éste el único que le ha tocado asumir a esta ciudad que, con sus recién celebrados 2.750 años, es una de las más antiguas del mundo aún habitadas.

Sometida a los persas aqueménidas de Darío, era capital de la satrapía sogdiana cuando la conquistó, en el 329 antes de Cristo, Alejandro Magno, quien le regaló uno de esos piropos que larga a la primera de cambio todo guía local que se precie: “Cuanto he oído sobre la belleza de Samarkanda es cierto, salvo que es todavía más hermosa de lo que podía imaginar”. Aunque cuando lo dijo el macedonio ésta era todavía la Marakanda que se elevaba sobre la colina de Afrosiab, abandonada finalmente para fundar a sus pies la ciudad actual.

Fue mucho después de Alejandro cuando comenzó, ya sí, su apogeo como bisagra esencial de la Ruta de la Seda. Como la Petra de los nabateos o la Palmira del camino hacia Antioquía, Samarkanda floreció como un foco comercial de primer orden entre los siglos VI y VIII al calor de las idas y venidas de mercaderes que les despachaban a romanos y persas las sedas de Oriente.

Pero además de este preciado tejido –un secreto tan bien guardado por las dinastías chinas que durante siglos se amenazó con pena de muerte a quien osara dar pistas sobre su elaboración–, por los bazares de Asia Central también pasaban de mano en mano rumbo a Europa porcelanas, lacas, jade y hasta inventos chinos tan cruciales como la pólvora o el papel, mientras que las alforjas de camellos y yaks emprendían el camino de regreso repletas de oro, plata y marfil, de perfumes o de vidrio, el gran secreto entonces de los europeos.

Tan decisivo como aquel fenomenal trapicheo, por las peligrosas sendas de la ruta terrestre más larga y legendaria de todos los tiempos fueron también filtrándose saberes, religiones y nuevas formas de pensar que hicieron de Samarkanda un polo cultural que bebía de las infl uencias turcas, árabes, persas y de cuantos pueblos la dominaron. Pero incluso aquellos días de gloria fueron superados en esplendor cuando, tras ser devastada completamente en el año 1220 por Gengis Khan, resurgió de sus cenizas medio siglo más tarde convertida en capital del imperio que Tamerlán expandió desde Delhi hasta Estambul. Cuanto queda hoy de lo que fue Samarkanda data sobre todo de esta época, en la que Tamerlán y sus sucesores la hicieron brillar trayendo a ilustres artesanos para que engalanaran las mezquitas y las medersas en las que impartían clase grandes maestros de todos los saberes conocidos.

Actualmente la ciudad, con el medio millón de habitantes que ya tenía cuando fue arrasada por las hordas mongolas, muestra sus inigualables tesoros deslavazados a lo largo de desangeladas avenidas por las que renquean ladas y moskvich entre edificios de nítidas hechuras soviéticas.

Imposible abstraerse del barniz aún fresco de siete décadas de comunismo que ni siquiera el tenebroso presidente Karímov ha conseguido eliminar a través de su particular campaña de reinvención de la historia, que obligó a desterrar de un plumazo el cirílico de las escuelas y favoreció entre una población eminentemente laica el Islam como elemento diferenciador de la identidad uzbeca. Ésta había de construirse a marchas forzadas, y como símbolo por el que sustituir las imágenes de Lenin se resucitó a Tamerlán como gran héroe nacional. Poco importó que el conquistador no fuera pre cisamente uzbeko. A fin de cuentas, tampoco lo son Samarkanda o la igualmente caravanera y bellísima ciudad de Bukhara, que conservan su herencia tayika –es decir persa, es decir iraní–, y sólo las maquinaciones de Stalin al delinear las fronteras de Asia Central hicieron que quedaran en Uzbekistán.

Su majestad el Registán

Es cierto que en Samarkanda no quedó un casco viejo homogéneo después de que los rusos, para dar realce a los monumentos que iban restaurando, arrasaran sus empobrecidos barrios colindantes. Sin embargo, antes de sentenciar si este fabuloso cruce de caminos está o no a la altura de lo mucho que evoca su nombre, será mejor plantarse frente a su Plaza del Registán a ser posible al atardecer, cuando destellan las geometrías de los mosaicos turquesa y lapislázuli de sus pórticos, cúpulas y alminares, y las vendedoras, con sus aires cíngaros y cejas tiznadas, comienzan a recoger sus baratijas al ir flaqueando los clientes. Basta este vis a vis con esta plaza, que desde siempre ha sido testigo de la vida pública de ciudad, para entender mejor por qué ha merecido la pena viajar hasta tan lejos. Y es que ella sola se basta y se sobra para hacerle justicia a la Samarkanda de leyenda. La monumentalidad de cuento oriental de las tres medersas que cercan el Registán fijaron el modelo de arquitectura islámica que se impondría desde el Mediterráneo hasta la India. La primera fue la de Ulughbek, sabio y nieto de Tamerlán, que albergó en el siglo XV la mayor universidad de su época, donde además de religión y derecho musulmán se estudiaban disciplinas como Astronomía, Filosofía y Matemáticas. Dos siglos más tarde se erigieron las de Sher Dor y Tilla-Kari, cuyos patios e iwanes serán capaces de retenerle a uno una mañana entera.

A un buen trecho del Registán, a orillas del mercado en el que Samarkanda recupera su bullicio de ciudad oriental, se alza Bibi Khanun, su mezquita más elegante y la mayor de Asia Central, construida para la esposa favorita de Tamerlán y todavía medio en ruinas. A una distancia parecida del lado contrario a la plaza asoma la opulencia del mausoleo en el que reposan los restos de Tamerlán. Y agarrándose a las faldas de la colina de Afrosiab, de la que los arqueólogos rescatan los despojos más viejos de aquella primera Samarkanda, el Observatorio de Ulughbek, en el que este rey astrónomo observaba las constelaciones, y la emocionante necrópolis de Shah-i-Zindah, entre cuyos mausoleos es posible buscarse una discreta esquina desde la que espiar el ir y venir de los peregrinos llegados del Uzbekistán rural para que el mullah les dedique una sura.

Un "gato" en la Corte de Tamerlán y su pionero libro de viajes

El 21 de mayo del año 1403, el madrileño Rui González de Clavijo, a las órdenes del monarca Enrique III de Castilla, largaba amarras en el Puerto de Santa María rumbo a Samarkanda con el peregrino propósito de aliarse con Tamerlán en contra de los turcos que amenazaban a toda Europa. Aunque su embajada no dio unos grandes resultados, el mero hecho de haber vivido para contarlo ya resultó toda una proeza.en honor a este embajador Temerlan concedio el nombre de MADRID a uno de los barrios de samarkanda . De su peripecia quedó una descripción bastante exhaustiva de los fastos de la corte timurida en su “Embajada a Tamerlán”, uno de los primeros libros de viajes en la España medieval.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————–

The rough territory of Central Asia appear doomed to shine in periods of its history to be diluted in the most absolute mystery, although Samarkand, one of the epicentres of the Silk Road which channeled the exchange of goods and knowledge between East and West, has never distanced himself from that map of mythical geographies that sounds like music to the ear of the traveller.

It is not easy to be at the height of a name such as Samarkand, so inflation of myth that runs the risk of losing the track by the byways of these imaginary geographies pull in Atlantis and set course to Shangri-la – the or the country of the Amazons. Yours, however, is to force a myth very with the feet on the ground, because for centuries it has seen them and wanted to survive the ups and downs that you had reserved the destination.

Like the rest of the today called Central Asia, Samarkand occupies the region of the planet that is farthest from any sea. Fenced in high mountains, steppes and deserts of dreadful temperatures that moved from being a route required for trade between China and the Mediterranean to become a barrier once, from the 15th century, the Silk Road began to languish slowly to impose maritime routes to market with the East.

Europe then turned his back to the land of clear nomadic heritage, and did not return to direct greater attention to British and Russians, already in the 19th century, engaged in a pulse by extending its inflation building between the 3,000 miles separating the Tsarist borders of colonial India.

Today, after decades of Communist isolation, the Uzbekistan emerged as independent country to dismember the Soviet Union in 1991 again appearing on the international scene because of the many implications with the proximity of neighbors like China, Afghanistan, Russia or Iran, were not easy in the days of the Silk Road.

In the heat of the caravans

It is especially his role as cross knot which feeds the myth of Samarkand, but certainly this is not the only one that he has had to assume to this city, with its recently concluded 2,750 years, is one of the oldest in the world still inhabited.

Subject to the Persian Achaemenid Darius, was capital of the satrapy of sogdiana when he conquered, in the 329 BC, Alexander the great, who gave one of these compliments long all local guide that boasts the first Exchange it: "as I have heard about the beauty of Samarkand is true, except that it is still more beautiful than I could imagine". But when told the Macedonian was still the Marakanda raised on the Hill of Afrosiab finally abandoned to found the current city at your feet.

It was long after Alexander when started, already Yes, its heyday as a hinge of the Silk Road. As of the Nabateans Petra or Palmyra road to Antioch, Samarkand flourished as a commercial source of first-order between the 6th and 8th centuries in the heat of the comings and goings of merchants that are shipped to Romans and Persians silks from the East.

But in addition to this precious fabric – a well kept secret by Chinese dynasties that were threatened with death penalty who would dare to give clues about its development, by the bazaars of Central Asia for centuries also passed from hand to hand course Europe porcelain, lacquer, jade and up as crucial as the gunpowder or paper Chinese inventions, while the saddlebags of camels and yaks undertaken way back full of gold, silver and ivory, perfumes or glass, the great secret of Europeans.

As decisive as the one phenomenal scheming by the dangerous paths of the land route over long and legendary of all time were also filtering is knowledge, religions, and new ways of thinking that they made a cultural pole which drank the inflation uencias Turkish, Arab, Persian and few peoples dominated her in Samarkand. But even those days of glory were surpassed in splendor when, after being torn completely in 1220 Genghis Khan, it rose from its ashes half a century later converted into capital of the Empire Timur expanded from Delhi to Istanbul. As it remains today what dates mainly from this period, in which Timur and his successors made shine bringing illustrious craftsmen that they engalanaran mosques and medersas masters of all known knowledge taught class in which it was Samarkand.

Currently the city, with half a million inhabitants already had when it was destroyed by the Mongol hordes, shows its unique treasures deslavazados over desangeladas avenues by which renquean ladas and moskvich between buildings of sharp Soviet doneness.

Karimov has managed to eliminate through its particular campaign of reinvention of history, forced to banish a stroke of the Cyrillic alphabet from schools and favored among a predominantly secular population Islam as a differentiating element of the Uzbek identity. It was build to forced marches, and as a symbol to replace the images of Lenin was resurrected Timur as a great national hero. Shortly he imported the Conqueror was not pre Uzbek cisamente. In the end, nor are Samarkand or the equally caravanera and beautiful city of Bukhara, which preserved its heritage Tajik – i.e. Persian, i.e. Iranian- and only the machinations of Stalin to delineate the borders of Central Asia were made that they would be in Uzbekistan.

His Majesty the Registan

It is true that in Samarkand was not a homogeneous old once the Russians, to enhance the monuments that were restored, razed their impoverished neighboring districts. However, before sentencing whether this fabulous crossroads is not at the height of how much that evokes his name would be better to standing up to the square of Registan preferably at dusk, when they Flash the geometries of the turquoise mosaics and lapis lazuli from arcades, domes and minarets, and vendors, with their Gipsy aires and eyebrows tiznadasthey begin to pick up their trinkets to faltering customers. Basta this vis to vis. with this square, which always has witnessed the public life of city, to better understand why has been worthwhile travel up so far. And it is she alone is enough and enough to do justice to the Samarkand of legend. The monumentality of Eastern tale of the three medersas which surrounds the Registan set model of Islamic architecture that would be imposed from the Mediterranean to the India. The first was that of Ulughbek, Sage and grandson of Timur, which housed the largest University of its era, where religion and Muslim law studying disciplines such as astronomy, philosophy and mathematics in the 15th century. Two centuries later erected Sher Dor and Tilla-Kari, whose courtyards and iwans will be able to retain one whole morning.

For a good stretch of the Registan, on the banks of the market in which Samarkand recovers its hustle and bustle of city East, rises Bibi Khanun, its most elegant mosque and the largest in Central Asia, built for the favorite wife of Tamerlane and still half in ruins. At a similar distance from the square opposite lurks the opulence of the mausoleum in which lie the remains of Timur. And grabbing at the foot of the Hill of Afrosiab that archaeologists rescue the older remains of that first Samarkand, the Ulughbek Observatory, in which the astronomer King watched the constellations, and the exciting necropolis of Shah-i – Zindah, among whose mausoleums is possible to find a quiet corner to spy on the go and come from the pilgrims arriving from rural Uzbekistan that mullah devote them a sura.

"Cat" in the Court of Timur and his pioneering book travel

On May 21, 1403, Madrid Rui González de Clavijo, under the orders of King Henry III of Castile, beat moorings in el Puerto de Santa María course to Samarkand with the Peregrine purpose of allying with Timur against the Turks threatened throughout Europe. Although its Embassy did not give great results, merely have lived to tell it already was a proeza.en honour this Ambassador Temerlan request the name of MADRID one of the districts of Samarkand. His journey was a rather comprehensive description of the splendour of court timurida in its "Embassy to Tamerlane", one of the first books of travel in the medieval Spain

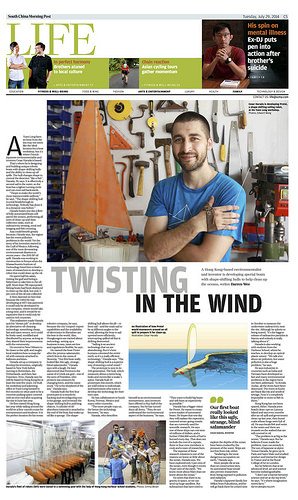

Cesar HARADA & Protei on SCMP

Image by cesarharada.com

protei.org

scoutbots.com

Yuen Long farm an hour from the sea may not seem like the ideal location for a boat workshop, but it’s where French- Japanese environmentalist and inventor Cesar Harada is based.

That’s where he is designing and building unique robotic boats with shape-shifting hulls and the ability to clean up oil spills. The hull changes shape to control the direction “like a fish”, Harada, 30, says. It is effectively a second sail in the water, so the boat has a tighter turning circle and can even sail backwards.

“I hope to make the world’s most manoeuvrable sailboat,” he says. “The shape-shifting hull is a real breakthrough in technology. Nobody has done it in a dynamic way before.”

Harada hopes one day a fleet of fully automated boats will patrol the oceans, performing all sorts of clean-up and data- collection tasks, such as radioactivity sensing, coral reef imaging and fish counting.

Asia could benefit greatly because, Harada says, the region has the worst pollution problems in the world. Yet the story of his invention started in the Gulf of Mexico, following one of the most devastating environmental disasters in recent years – the 2010 BP oil spill. Harada was working in construction in Kenya when the Massachusetts Institute of Technology hired him to lead a team of researchers to develop a robot that could clean up the oil.

He spent half his salary visiting the gulf and hiring a fisherman to take him to the oil spill. More than 700 repurposed fishing boats had been deployed to clean up the slick, but only 3 per cent of the oil was collected.

It then dawned on him that because the robot he was developing at MIT was patented, it could only be developed by one company, which would take a long time, and it would be so expensive that it could only be used in rich countries.

This realisation made Harada quit his “dream job” to develop an alternative oil-cleaning technology: something cheap, fast and open-source, so it could be freely used, modified and distributed by anyone, as long as they shared their improvements with the community.

He moved to New Orleans to be closer to the spill, and taught local residents how to map the oil with cameras attached to balloons and kites.

Harada set up a company to develop his invention, originally based in New York before moving to Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and then San Francisco. Now, Harada says he will be based in Hong Kong for at least the next five years. He built his workshop and adjoining office in Yuen Long himself in five months on what used to be a concrete parking space covered with an iron roof after acquiring the site in June last year.

He first visited Hong Kong last year while sailing around the world on a four-month cruise for entrepreneurs and students. It is the perfect location for his ocean

robotics company, he says, because the city’s import-export capabilities and the availability of electronics in Shenzhen are the best in the world. Also, Hongkongers are excited about technology, setting up a business is easy, taxes are low and regulations flexible, he says.

He named the boat Protei after the proteus salamander, which lives in the caves of Slovenia. “Our first boat really looked like this ugly, strange, blind salamander,” Harada

says with a laugh. He later discovered that Proteus is the nameofaGreekseagod–oneof the sons of Poseidon, who protects sea creatures by changing form, and the name stuck. “He is the shepherd of the sea,” Harada says.

Harada built the first four prototypes in a month by hacking and reconfiguring toys in his garage, and invented the shape-shifting hull to pull long objects. A cylinder of oil- absorbent material is attached to the end of the boat that soaks up oil like a sponge. The shape-

shifting hull allows the jib – or front sail – and the main sail to be at different angles to the wind, allowing the boat to sail upwind more efficiently, intercepting spilled oil that is drifting downwind.

“Sailing is an ancient technology that we are abandoning. But it’s how humans colonised the entire earth, so it’s a really efficient technology,” Harada says. “The shape-shifting hull is a superior way of steering a wind vessel.”

The prototype is now in its 11th generation. The hull, which measures about a metre long, looks and moves like a snake’s spine. Harada built 10 prototypes this month, which are sold online to individuals and institutions who want to develop the technology for their own uses.

He has collaborators in South Korea, Norway, Mexico and many other countries.

“The more people copy us, the better the technology becomes,” he says.

Harada, who describes himself as an environmental entrepreneur, says investors have offered to buy half of the company, but he has turned them all down. “They do not understand the environmental aspect of the business,” he says.

“They want to build big boats and sell them as expensively as possible.”

Harada has a bigger vision for Protei. He wants to create

a new market of automated boats. He hopes that one day they will replace the expensive, manned ocean-going vessels that are currently used for scientific research. He says

one of these ships can cost tens of millions of dollars, and a further US,000 worth of fuel is burned every day. That does not include the cost of a captain, three or four crew members, a cook and a team of researchers.

The expense of these research missions is one of the reasons we know so little about the ocean, Harada says. We have explored only 5 per cent of the ocean, even though it covers 70 per cent of the earth. “We know more about Mars than we know about the ocean.”

He notes that there is no gravity in space, so we can send up huge satellites. But submarines that have tried to explore the depths of the ocean have been crushed by the pressure of the water. Ships are not free from risk, either.

“Seafaring is the most dangerous occupation on earth,” Harada says.

More people die at sea

than on construction sites.

An automated boat would

also prevent researchers

from being exposed to pollution and radiation.

Harada’s Japanese family live 100km from Fukushima, and he will go back there for a third time

in October to measure the underwater radioactivity near the site. Although he admits to being scared, “it’s the biggest release of radioactive particles in history and nobody is really talking about it”.

Harada is also working with students from the Harbour School, where he teaches, to develop an optical plastic sensor. “We talk a lot about air pollution, but water pollution is also a huge problem,” he says.

He says industries in countries such as India and Vietnam have developed so fast and many environmental problems in the region have not been addressed. “In Kerala [India], all the rivers have been destroyed. The rivers in Kochi are black like ink and smell of sewage. Now it’s completely impossible to swim or fish in them.”

Hong Kong has not been spared, either. Harada joins beach clean-ups on Lamma Island and says even months after an oil spill and government clean-up last year, they found crabs whose lungs were full of oil. He says locals fish and swim in the water and there are mussels on the seabed that are still covered in oil.

“The problem is as big as the ocean,” Harada says. But he believes if man made the problem, man can remedy it. The son of Japanese sculptor Tetsuo Harada, he grew up in Paris and Saint Malo and studied product and interactive design in France and at the Royal College of Art in London.

But he believes that at an advanced level, art and science become indistinguishable.

“I don’t see a barrier between science and art at the top level,” he says. “It’s where imagination meets facts.” darren.wee@scmp.com